Georgia O’Keeffe Exhibition at Tate Modern, London

Back in 2016, Tate Modern held an impressive Georgia O’Keeffe exhibition. There are no paintings by O’Keeffe in any British collection, so this was an exciting opportunity to see a major collection of her work all in one place.

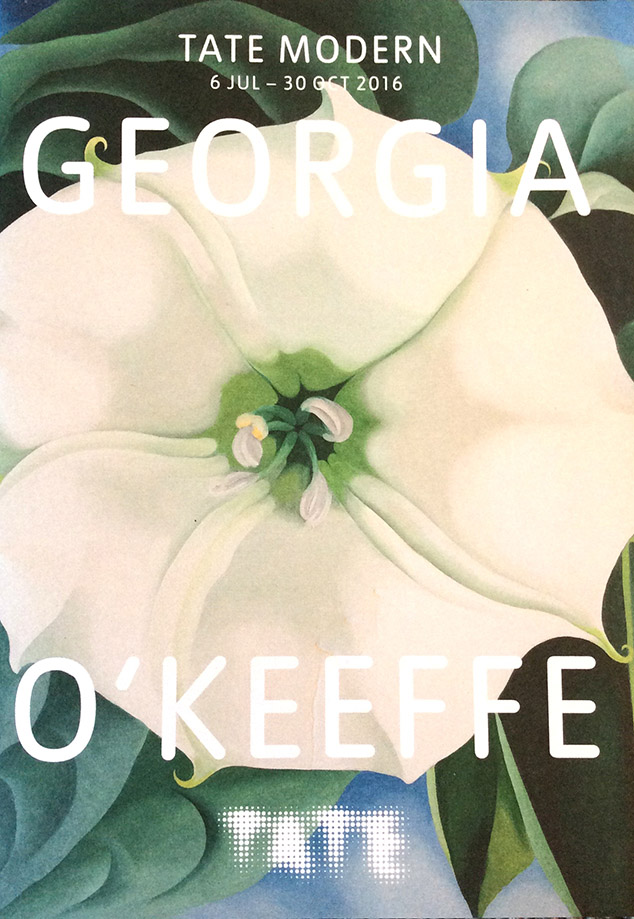

Note: Photography was not permitted in this exhibition so all my images are taken from the official Tate postcards.

No matter what exhibition I go to see, anticipation gives way to excitement as all sorts of thoughts rush through my head. Which artworks are going to be on display? Just how big are my favourite paintings? Will they be as impressive as the images in my head? How will they be displayed? Will each work of art have its own wall, or will they be clumped together? My feelings were no different on entering the Georgia O’Keeffe exhibition at London’s Tate Modern.

I have loved Georgia O’Keeffe’s work ever since I studied her when doing my A-levels. Unlike the famous flower canvases that she is renowned for, I came across her when doing a project on cityscapes. I fell in love with her Manhattan skylines. I also visited New York around the same time and recreated some of her cityscapes in soft pastel, my preferred medium at the time.

I was delighted to find one of the 13 galleries early on in the exhibition dedicated to her New York works, with three of her stunning portrait towering skyscraper canvases adorning one wall. I was gutted not to see my two favourites: ‘Radiator Building, Night New York, 1927′ and ‘The Shelton with Sunspots, 1926’, but the others were all I’d dreamed they would be.

On entering the Georgia O’Keeffe exhibition you were given a booklet of information which gives excellent succinct information about her life and the works on show. It was the same information that was displayed on wall boards in the exhibition and is great for revisiting at a later date.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Early Work

Georgia O’Keeffe is widely recognised as a foundational figure within the history of modernism in the U.S. and became an American icon. The Tate’s exhibition revisited the six most productive decades of her work: the 1910’s to the 1960’s. The first ever showing of her work was at Alfred Steiglitz’s New York gallery “291” in 1916, so this exhibition celebrated a century of O’Keeffe and aimed to dispel the clichés that persist about her painting.

The first few rooms in the exhibition clocked O’Keeffe’s early work, initially in charcoal. This work brought her to the attention of Alfred Steiglitz, renowned photographer of the ‘progressive era’. She had a personal as well as a professional relationship with him, with them eventually getting married. The exhibition showed works by Steiglitz here too as his work often influenced hers.

O’Keeffe’s New York Work in the 1920’s

O’Keeffe turned to greater abstraction in the 1920’s, taking inspiration from the landscape and an interest in synaesthesia – the stimulation of one sense by another: “the idea that music could be translated into something for the eye.” These compositions often contained suggestive shapes of the female form and hinted at erotic content and phallic symbols. This view of her work frustrated O’Keeffe and she is recorded as saying: “When people read erotic symbols into my paintings, they’re really talking about their own affairs.”

During the period when O’Keeffe and Steiglitz lived in New York City on the 30th floor of a skyscraper, it was visits to rural upstate New York, to Lake George where the Steiglitz family had a summer home that brought O’Keeffe’s attention back to nature. The years she spent summering at Lake George became the most prolific of her career. It was here where she found the subjects that brought her widespread critical acclaim. From the hill overlooking the lake and surrounding gardens, orchards and woods, she found the flowers, trees, leaves, skies and landscapes that dominate her output through the 1920’s.

It was her treatment of these conventional subjects that brought her to the forefront – the application of abstraction, the bold use of colour and the modern treatment of composition which saw magnificent flowers billowing out across and beyond the canvas edges. Two of her most famous flower paintings are here in the exhibition: ‘Jimson Weed/White Flower No.1′ and ‘Oriental Poppies’.

O’Keeffe developed her once abstract flower paintings into close up work with greater realism, focusing on the flower blooms themselves. She did this as a means of dispelling the erotic interpretations of her work that critics had established.

The Influence of New Mexico in O’Keeffe’s Work

One thing I knew about Georgia O’Keeffe before my visit to the Tate exhibition was that she lived a great proportion of her life in New Mexico. However I did not know anything about the types of painting she moved to do once under the influence of the American Southwest.

The rest of the exhibition concentrates on the subject matters directly influenced by New Mexico. As there were few flowers there, she would gather bones from the desert to paint instead. Mountain vistas became prevalent, particularly the mesa (wide topped hill) viewed from the house she bought on Ghost Ranch in 1940. You can see this in the painting she called ‘My Front Yard, Summer 1941’. She painted this subject in all manners and colour schemes while joking: “It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me…God told me if I painted it enough I could have it.”

Another mountain subject O’Keeffe painted again and again was known as the ‘Black Place’ which was 150 miles west of her home at Ghost Ranch. On discovering it she insisted on returning to paint it. Even in the blisteringly hot summers it quickly become one of her favourite places to paint. In the ‘Black Place’ series of paintings displayed in the Tate’s exhibition, it shows how she progressively abstracted from observed reality to more intensely coloured non-naturalistic compositions which she painted from memory – from ‘Black Place 1’ in 1944 to ‘Black Place Green’ in 1949.

Pelvic Bones and More Abstraction from the 1940’s and 50’s

Gallery 11 displayed three different series of paintings made in 1940’s and 50’s. Particularly striking, though I’m not sure I personally like them, was the Pelvis series painted in the 1940’s. Working in series was now the approach that O’Keeffe applied to her work and it seems that her work was edging nearer and nearer to abstraction once again, in parallel with developments in American abstract painting. Moving from skull bones to pelvic bones, O’Keeffe was most interested in the holes in the bones and what she could see through them, rather than the bones themselves.

In the wake of World War II O’Keeffe painted a series of pelvic bones held against a blue sky saying: “they were most beautiful against the Blue – that Blue that will always be there as it is now, after all man’s destruction is finished”. One even featured the Ghost Ranch mesa. I preferred the Cottonwood series of trees which are much like the early flower abstractions.

O’Keeffe’s Late Work from the 50’s and 60’s

The final room of the exhibition showed O’Keeffe’s late paintings from the 1950’s and 60’s. There were works which resemble aerial views of rivers, but my eye was immediately drawn to the painting ‘Sky Above the Clouds III’ which represents the view looking down on clouds taken from a plane.

It seemed a fitting way to finish the exhibition! Not only does her work move in a full circle – from abstraction, back to abstraction (granted of a different style); but the views from a plane seem to distance the viewer once again from her work. We were geographically distant from O’Keeffe’s work before the exhibition due to no paintings of hers residing in the UK. Then our journey through the exhibition pulled us in for a full exploration of her life and work. You really felt like you’d gotten to grips with her connection to the landscape – like you were really in New Mexico; so that the view from the plane is you flying home, in parallel with the works physically flying home from London to their original collections after the exhibition.

Most of the works in this Georgia O’Keeffe exhibition originated in the U.S.A. with many from the O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico. This is a place I would love to visit, even more so after experiencing Tate Modern’s excellent exhibition.

Get in Touch…

I hope my post has widened your knowledge of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work. I don’t know about you, but I was pleasantly surprised by the extent of subject matters she painted. Did you visit this exhibition when it was on in 2016? Are you familiar with the full range of O’Keeffe’s work? Drop me a line in the comments below as I’d love to hear your thoughts…

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please subscribe to my blog via email over on my profile page to receive notifications of when new posts go live. You can also sign up to receive my newsletter, or follow me through Bloglovin’. Then head on over to Facebook, Instagram or Twitter to keep up with all my travel related news. Hope to see you there.

Further Reading…

I go to so many galleries and exhibitions as it’s one of my favourite things to do, however I unfortunately haven’t written many of these up over the years. What I do though, is document what galleries and exhibits I’ve visited in my monthly newsletter which I started in 2021 – check out what kind of things I cover here to see if you wish to sign up!

In the meantime, I have written posts on the Millennium Galleries in Sheffield and the Harris Museum and Art Gallery in Preston. You can also find out more about the National Museum Cardiff in my post on the best things to see and do in Cardiff.

If ceramics are up your street, then have a look at the ‘Potfest in the Park’ Ceramics Festival which occurs annually at the stunning Hutton-in-the-Forest Country Estate in Cumbria.

Discover modern monumental sculpture in the great outdoors with The Dream sculpture in Merseyside, the Knife Angel which tours the country, but which I saw at its first location in Liverpool, the Halo panopticon sculpture in Lancashire, and Antony Gormley’s ‘Another Place’ Iron Men on Crosby Beach in Merseyside.

PIN FOR LATER!

2 COMMENTS

Leave A Comment

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

georgina | 25th Aug 25

Hi Tilly, i too went to the exhibition in 2016, i had not been feeling great and went with my girlfriend sun and i bought a book about her life and work. I remember thinking about myself alot and sun had been encouraging me to stop thinking about myself and think of the gallery around me as i had been not doing myself any good. I tried i did try and i remember having a great time thinking about georgia and what she did aside from paint and wanted to know all about her life. Thank you for sharing.

Tilly Jaye Horseman | 22nd Sep 25

Lovely to hear from you Georgina. It was a fab exhibition and I’m glad it helped you. I hope you enjoyed the book you bought on her life. I have a few in my collection. All the best, Tilly x